Method Article

静脉-动脉体外膜肺氧合治疗心源性休克

摘要

以下文章重点介绍了心源性休克患者启动和维持静脉-动脉体外膜肺氧合所涉及的各种步骤。

摘要

心源性休克 (CS) 是一种以低心输出量情况下组织灌注不足为特征的临床病症。CS 是急性心肌梗死 (AMI) 后死亡的主要原因。几种临时机械支持装置可用于 CS 的血流动力学支持,直到临床恢复或直到进行了更明确的外科手术。静脉-动脉 (VA) 体外膜肺氧合 (ECMO) 已发展成为难治性 CS 短期循环支持的强大治疗选择。在没有随机临床试验的情况下,ECMO 的使用以临床经验为指导,并基于登记处和观察性研究的数据。使用 VA-ECMO 出院的存活率为 28-67%。ECMO 的启动需要静脉和动脉插管,这可以通过经皮或手术切除进行。ECMO 回路的组成部分包括从静脉系统抽血的流入插管、泵、氧合器和将血液回流到动脉系统的流出插管。ECMO 启动后的管理考虑包括全身抗凝以预防血栓形成、促进心肌恢复的左心室卸载策略、在股动脉插管的情况下使用远端灌注导管预防肢体缺血,以及预防其他并发症,例如溶血、空气栓塞和 Harlequin 综合征。ECMO 禁用于无法控制的出血、未修复的主动脉夹层、严重主动脉关闭不全以及徒劳的病例,例如严重的神经损伤或转移性恶性肿瘤。在考虑患者进行 ECMO 时,建议采用多学科休克小组方法。正在进行的研究将评估增加常规 ECMO 是否能提高接受血运重建的 AMI 合并 CS 患者的生存率。

引言

心源性休克 (CS) 是一种以低心输出量情况下组织灌注不足为特征的临床病症。尽管再灌注治疗取得了进展,但急性心肌梗死 (AMI) 仍然是 CS 的主要原因。根据对全国住院样本 (NIS) 数据库的分析,该数据库从大约 20% 的美国住院病例中收集数据,55.4 年至 144,254 例 CS 病例中有 2005% 继发于 AMI1。CS 的其他病因包括失代偿性心力衰竭、暴发性心肌炎、心脏切开术后休克和肺栓塞 (PE)。CS 与高院内死亡率相关,范围在 45-65% 之间 1,2。因此,快速识别 CS 并纠正可逆原因对于提高患者生存率至关重要。例如,我们应该紧急血运重建用于心源性休克的闭塞冠状动脉 (SHOCK) 试验表明,与 CS 并发 AMI 患者的初始医疗稳定策略相比,早期血运重建策略与 6 个月3 和 1 年4 的生存率更高相关。

血管加压药和正性肌力药可用于纠正与 CS 相关的低血压,但均未显示对死亡率有任何益处 5,6,7。另一方面,短期机械循环支持 (MCS) 设备可以为难治性 CS 患者提供血流动力学支持,作为恢复的桥梁或通往更确定性治疗的桥梁。近十年来,MCS 的使用有所增加;然而,CS 住院的发生率超过了 MCS8 的使用率。血管内微轴左心室辅助装置 (LVAD)(例如 Impella 和 TandemHeart)和静脉-动脉体外膜肺氧合 (VA-ECMO) 的应用相对增加抵消了主动脉内球囊泵 (IABP) 利用率的下降趋势。

VA-ECMO 可以产生高达 4-6 L/min 的流量,其在 CS 中的应用已广受欢迎9。根据体外生命支持组织 (ELSO) 维护的全球登记处,VA-ECMO 的使用量从 2010 年之前的每年不到 500 次增加到 2015 年的 2,157 次10。尽管如此,VA-ECMO 是一种资源密集型模式,需要全天候提供专业设备和训练有素的员工。因此,在开始和维持 ECMO 之前,患者选择至关重要,以改善结果并最大限度地减少不良事件。本文讨论了 VA-ECMO 启动所涉及的步骤、启动后维护、其使用的证据以及相关并发症。

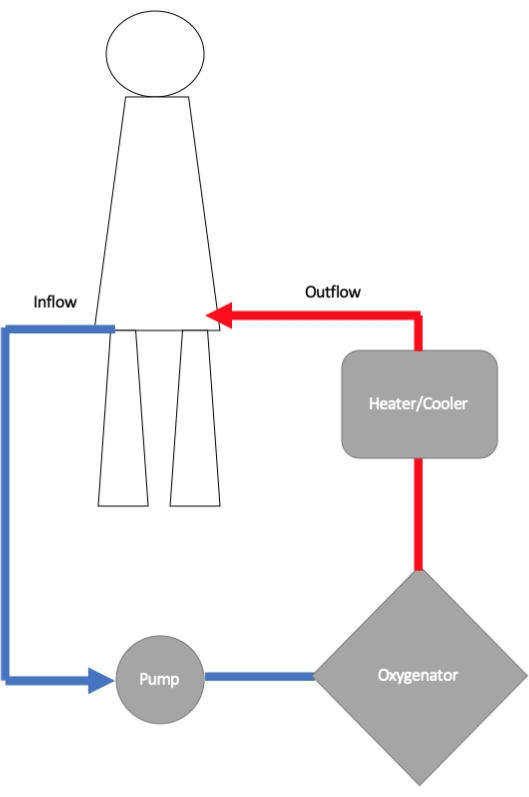

ECMO 回路由流入插管、离心泵、氧合器和流出插管组成(图 1)11。流入套管 通过 管道连接到离心泵,离心泵中旋转的转子产生流量和压力。血液从泵流向膜氧合器,在那里进行气体交换12.在这里,血红蛋白被氧气饱和,氧合程度是通过改变流速和增加或减少供应给氧合器的吸入氧 (FiO2) 分数来控制的。通过调整通过氧合器的逆流气体的扫描速度来控制二氧化碳的去除。通常将热交换器连接到氧合器上,因此可以调节返回体内的血液温度。血液从氧合器通过流出套管返回给患者,流出套管位于股动脉外周或主动脉中央。

研究方案

该协议遵循内布拉斯加大学医学中心机构人类研究伦理委员会的指导方针。

1. 患者选择

- 当预计心肌功能在初始损伤后会改善时,考虑对难治性 CS 患者进行 VA-ECMO 作为恢复的桥梁,作为决策的桥梁,或作为通往更确定性治疗的桥梁,例如当心肌功能障碍不可逆时,作为通往更确定性治疗的桥梁,例如持久 LVAD 或心脏移植。

注:各种适应症包括继发于 AMI 的 CS、终末期心力衰竭、暴发性心肌炎和大面积 PE 引起的肺心病 13,14,15,16,17。另一个越来越使用的领域是接受心脏手术的患者,这些患者在心脏切开术后出现难治性 CS18。 - 作为体外心肺复苏 (ECPR) 的一部分,在继发于难治性心室颤动/室性心动过速的特定院外心脏骤停患者中使用 VA-ECMO 进行心肺支持。

注意:有限的证据表明 ECPR 与提高生存率相关,现已纳入 CPR指南 19,20。 - 在涉及限制生存的严重不可逆终末器官衰竭的情况下,例如晚期恶性肿瘤、脑损伤、主动脉夹层,以及当患者的护理目标与 MCS21 的使用不一致时,避免使用 VA-ECMO。

注意:一些相对禁忌症包括阻碍插管的外周血管疾病、不受控制的出血或使用抗凝剂的禁忌症。高龄 (>70 岁) 不是绝对禁忌证;然而,与年轻人22 相比,这一人群的院内生存率历来较差。

2. VA-ECMO 的插管和启动

- 在开始 CS 患者接受 VA-ECMO23 之前,促进由高级心力衰竭专家、介入心脏病专家、心胸外科医生和重症监护重症监护医师组成的跨学科团队讨论。

- 在心导管室、急诊科或重症监护病房进行经皮入路(外周插管)或手术室进行手术入路(中央插管)24。

- 对于经皮入路,使用消毒溶液(如洗必泰)清洁和准备通路部位。

- 在超声引导下,使用带有针头的改良 Seldinger 技术获得股静脉通路,并放置 5 Fr 微护套25。

- 将灵活的 J 型尖端导丝(0.038 英寸 x 180 厘米)穿过股静脉进入下腔静脉 (IVC) 并将其引导至右心房。

- 使用顺序扩张器扩张静脉通路部位,连续扩张套管通道,增加一个扩张器(2 Fr 尺寸)。然后放置一个适当大小的静脉插管(单腔)。

注意:套管的大小是根据超声上血管的年龄、性别和直径以及所需的流量来确定的。静脉插管有 21 Fr 到 25 Fr 的尺寸,而 25 Fr 插管通常足以满足大多数成年人的需求。 - 通过透视或平片 X 光检查确认静脉插管的尖端位于 IVC 肝内部分和右心房的交界处。

- 使用改良的 Seldinger 技术以类似的方式获得动脉通路,通常在对侧股动脉中,然后放置微护套 (5 Fr)。

- 将柔性 J 形尖端导丝 (0.038 英寸 X 180 厘米) 或刚性导丝推进股总动脉,然后进入主动脉。

- 在用扩张器进行皮肤和皮下组织进行扩张后,放置适当大小 (15-21 Fr) 的动脉插管。

注意:选择套管尺寸以提供 >2.4 L/min/m2 的心脏指数。19 Fr 动脉插管将为大多数成人提供足够的支撑;但是,对于体型较小的女性,应使用较小尺寸的套管。 - 使用微穿刺针通过改良的 Seldinger 技术,将远端灌注导管 (DPC) 放置在同侧股浅动脉中进行顺行灌注。引入一个 5 Fr DPC 并使用 6-7 英寸延长管26 将其连接到动脉插管的侧端口。

注意:逐渐变大的动脉插管会增加同侧肢体缺血并发症的风险,尤其是在患有潜在外周血管疾病的患者中。 - 用不可吸收的 2.0 丝缝合线将静脉和动脉插管缝合到皮肤上,将静脉和动脉插管固定到位。

注意:中央插管通常在手术室进行,通常需要胸骨切开术。 - 开胸术后对右心房和主动脉进行直接插管。使用 purse-string 4.0 prolene 缝合线、紧贴器和水龙头将它们固定到位。

- 然后,使用多条缝合线从空腔内将插管固定到胸壁上。

- 用封闭敷料保持胸部开放或在结束时闭合。当胸部闭合时,将插管穿过皮肤。

- 将插管(动脉和静脉)连接到 ECMO 回路并增加血流量,直到达到呼吸和血流动力学参数。

3. 启动后管理

- 患者监测

- 放置一根 7.5 Fr 肺动脉导管,通过定期测量肺动脉压和肺毛细血管楔压作为左心室充盈压的替代物,帮助临床决策。

注意:这有助于识别有发生肺水肿风险的患者,因为 VA-ECMO 通过从右心房引流静脉血并将含氧血液回流到髂动脉/降主动脉来形成从右向左的分流。虽然前负荷降低,但 VA-ECMO 后负荷的增加会增加已经存在潜在 LV 功能障碍的 CS 患者发生肺水肿的风险。 - 在导丝27 的帮助下,使用显微穿刺技术将动脉线放置在右侧桡动脉或左侧桡动脉中。

注意:这有助于确定分水岭的位置(主动脉弓中来自左心室的顺行血流与来自动脉插管的逆行血流相遇的区域)28。 - 监测右侧桡动脉部位的氧饱和度,以评估上半身(大脑和右上肢)氧合。每 8-12 小时进行一次动脉血气分析,以确保足够的氧合29。

- 调整氧合器上的 FiO2 (拨高旋钮)以保持 60-100 mmHg PaO2。

注:FiO2 通常在 VA-ECMO 开始时设置为 100%,随后随着氧合的改善而降低。 - 通过将清扫速度调整到 3-7 L/min 之间来纠正任何呼吸性酸中毒,从而优化通气,从而去除二氧化碳。

- 通过静脉气体分析连续监测终末器官灌注的标志物,如乳酸、SvO2、转氨酶和肌酐清除率30,31。

注意:目标 SvO2 应为 >70% 且乳酸低于 2.2 mmol/L。

- 放置一根 7.5 Fr 肺动脉导管,通过定期测量肺动脉压和肺毛细血管楔压作为左心室充盈压的替代物,帮助临床决策。

- 调整静脉喵喵的流量和管理

- 调整通过回路的流量以允许足够的终末器官灌注(目标流量为 60 cc/kg/min)。通过调整泵的速度来改变流量。插管后最初保持 4-6 L/min 的流量。

注意:泵速较高、血容量减少和静脉插管位置不当会导致静脉颤动,表现为静脉插管抽吸或“咕噜咕噜”32。静脉颤振会导致泵头产生真空,因为泵中的转子继续旋转并从泵中排出血液,从而导致溶血。 - 在低血容量病例中,通过液体复苏纠正静脉颤振。重新定位静脉插管,以防错位或扭结。在高速33,34 的情况下降低泵的速度。

- 通过将静脉储液器或可折叠膀胱连接到流入套管来最大限度地减少静脉颤动。这允许通过为泵提供体积来减少流入套管的吸力。

- 调整通过回路的流量以允许足够的终末器官灌注(目标流量为 60 cc/kg/min)。通过调整泵的速度来改变流量。插管后最初保持 4-6 L/min 的流量。

- 左心室卸载

注:逆行 VA-ECMO 血流的后负荷增加可导致 LV 舒张末期压 (LVEDP) 升高,从而加重肺水肿,严重的 LV 停滞病例可能导致停滞血液形成血栓35。- 为了减轻 LV 负荷并减少后负荷,使用正性肌力药物,如多巴酚丁胺(起始剂量为 1-2 μg/kg/min)或血管扩张剂,如肼屈嗪或硝酸盐 36,37,38。

注意:然而,这些通常是不够的,可能需要机械卸载 LV。 - 经皮放置心室支持装置(例如 Impella)或主动脉内球囊反搏器 (IABP),以完成 LV 的直接卸载。为了完成 LV 的间接卸载,经皮放置肺动脉插管或进行球囊隔膜造口术。

注意:手术技术,包括经房间隔左心房引流或 LV 心尖直接插管,也可用于 LV 卸载39。

- 为了减轻 LV 负荷并减少后负荷,使用正性肌力药物,如多巴酚丁胺(起始剂量为 1-2 μg/kg/min)或血管扩张剂,如肼屈嗪或硝酸盐 36,37,38。

- 抗凝

- 在插管时开始全身抗凝治疗。推注 50-100 IU/kg 静脉注射肝素(推荐),然后连续使用肝素,如下所示。

- 在实验室检查期间(每 4-6 小时),继续使用普通肝素以维持活化部分凝血活酶时间或活化凝血时间至少为正常上限的 1.5 倍。

- 在肝素诱导的血小板减少症患者中,使用直接凝血酶抑制剂,如比伐卢定(起始剂量为 0.025-0.05 mg/kg/h)40 或阿加曲班(起始剂量为 0.05-2 μg/kg/min)41 以达到治疗水平。

4. 并发症的预防和管理

- 丑角(南北)综合征

注意:在伴有呼吸衰竭的情况下,当分水岭(含有来自流出套管的含氧血液的逆行血与来自 LV 的顺行血液相遇的区域)位于主动脉弓分支血管起点的远端时,可发生上半身差异性紫绀。来自 LV 的脱氧血液通过颈动脉和锁骨下动脉供应上半身,而下半身由 VA-ECMO 流出套管的血液供应。这种现象称为丑角综合症或南北综合症(上半身是蓝色的,下半身是粉红色的)。- 如果患者接受机械通气,则通过增加 FiO2 或呼气末正压来增加回流至 LV 的血液的氧饱和度,或者通过将含氧血液回流至右心房来控制这种鉴别紫绀,通常是通过与 ECMO 回路动脉分支 (V-A-V ECMO) 相连的颈内静脉中引入的另一个套管。

- 每 8-12 小时从右侧桡动脉进行动脉气体分析 (ABG) 监测上半身氧合饱和度。ABG42 上 60-100 mmHg 的 PaO2 可确保足够的组织氧合。

- 下肢缺血

注意:外周动脉插管最严重的并发症之一是下肢顺行缺血,很少导致筋膜室综合征,在极端情况下,可能需要截肢43。肢体缺血的发生率是可变的,从 10% 到 70% 不等,如不同的研究所报告的那样 44。- 根据超声上股动脉的直径选择合适的套管尺寸,从而有可能减少下肢缺血并发症。

- 使用串联脉冲多普勒或近红外光谱 (NIRS) 监测插管后的下肢循环44。NIRS 是一种用于访问组织 oxygentaion45 的非侵入性成像工具。

- 使用 NIRS 对下肢组织氧合进行连续评估。将传感器垫放在连接到血氧仪的小腿肌肉上,以轻松检测组织氧合的任何变化,这是灌注的指标。

- 在 ECMO 插管时,将顺行灌注导管 (5-7 Fr) 插入股浅动脉,以防止下肢缺血并发症。

- 出血和溶血

注意:VA-ECMO 启动后轻微溶血很常见。严重溶血的原因包括泵血栓形成和 ECMO 回路中的凝血。- 仔细监测有临床意义的溶血。每天测量血红蛋白水平、乳酸脱氢酶、胆红素和肌酐。

- 考虑中断严重出血和血小板减少症患者的全身抗凝治疗46。然而,这可能会增加血栓形成并发症的风险;因此,在接受抗凝治疗之前,应仔细评估出血和血栓形成风险。

- 空气栓塞

注意:ECMO 回路中的空气滞留可能是由于连接松动、外周或中心静脉通路或氧合器膜破裂47 造成的。它会导致空气栓塞,如果气泡进入脑循环,可能会导致中风。- 在通气支持下将患者置于特伦德伦伯卧位,并夹住 ECMO 回路以管理空气栓塞

- 当怀疑空气栓塞时,应脱气并重新灌注回路。有时,整个电路可能需要更换。

5. 从 ECMO 撤机

- 一旦患者从促使使用 VA-ECMO 的初始损伤中恢复过来,就评估患者是否脱机。

注意:伴随的呼吸衰竭必须在脱机前解决。 - 进行连续超声心动图检查,以评估心脏功能的改善情况和脱机准备情况。

- 在患者脱离 VA-ECMO 之前确认血流动力学稳定性。

注意:患者必须恢复搏动动脉波形至少 24 小时,并且在没有或有低剂量血管加压药的情况下,平均动脉压应为 >60 mmHg48。 - 脱机时,进行超声心动图调节研究,其中 ECMO 流量逐渐减少至最低 1-1.5 L/min。确保血流动力学稳定,并在超声心动图上评估心脏功能。

注:在调节研究期间,左心室 (LV) 射血分数为 >20%-25%,主动脉速度-时间积分为 >10 cm,二尖瓣外侧环峰值收缩速度为 >6 cm/s 是成功脱机的预测因子49。 - 在患者脱机时监测终末器官灌注的实验室参数,例如乳酸、SvO2 和肾功能。

- 为了促进脱机过程,在拔管之前在患者和 ECMO 回路之间放置一个简化的脱机桥50 (此步骤是可选的)。

注意:脱机桥允许在 ECMO 支持下观察患者,并有机会在几分钟内在需要时重新打开 ECMO 回路。它由一根连接流入和流出套管的长管组成。 - 将夹子放在撤机桥近端的流入和流出套管上,朝向患者侧,从而将患者与 ECMO 回路分开,并允许血液在 ECMO 回路内再循环。

- 夹紧回路后,在拔管前观察患者长达 24 小时。如果需要血流动力学支持,只需取下管夹即可重新启动 ECMO 流量。

- 为了进一步增加脱机,使用可提供高达 5 L/min 流量的心室支持装置(例如 Impella)。在确保血流动力学稳定的同时,增加来自心室支持装置的流量并系统地降低 VA-ECMO 流量。

注意:心室支持装置的好处之一是它可以使用腋窝入路植入,从而允许在移除 VA-ECMO51 后早期行走。 - 一旦认为患者适合移除 VA-ECMO,应在手术室或心导管实验室进行拔管。

注意:大多数外周动脉插管患者需要一定程度的血管修复。

结果

根据各种观察性研究的报告,在难治性 CS 中使用 VA-ECMO 后出院的存活率为 28-67%13、15、52、53、54、55、56%(表 1)。结局因 CS 的病因而异。在 ELSO 登记处,从 9,025 年到 1990 年,2015 名成年人接受了体外生命支持 (ECLS) 的支持。CS 是与 ECLS 使用相关的最常见诊断,出院存活率仅为 42%10。患有心肌炎的成年人生存率最高 (65%),而患有先天性心脏缺陷的成人生存率最低 (37%)。心脏切开术后 CS 代表 VA-ECMO 开始后院内结局较差的另一人群,院内生存率在 30-40% 之间53,54。对 17 项研究的荟萃分析表明,与不卸载相比,VA-ECMO 中的 LV 卸载与死亡率降低相关57。VA-ECMO 本身的各种并发症可导致与 CS 相关的发病率和死亡率增加。例如,45-60% 的 ECMO 患者注意到出血事件58,59,较高的活化部分凝血活酶时间与出血并发症的风险增加有关。最近对 44 项研究60 项评估了难治性 CS 中使用 VA-ECMO 后的长期生存率的荟萃分析显示,1 年和 5 年的总生存率分别为 36.7% 和 29.9%。因此,尽管使用 VA-ECMO 作为 CS 患者的抢救方式,但院内和长期死亡率仍然很高。此外,一些证据表明,成功撤机 VA-ECMO 并不总是能预测生存率48。成功脱离 VA-ECMO 的患者的院内死亡率约为 25%61。最近一项针对 117 名患者的多中心随机对照 ECMO-CS 试验表明,与允许在血流动力学恶化的情况下下游使用 VA-ECMO 的早期保守管理相比,早期使用 VA-ECMO 治疗 D-E 期休克并没有改善临床结果62。相比之下,一项单中心随机对照 ARREST 试验63 表明,与标准高级心血管生命支持 (ACLS) 治疗相比,早期 ECMO 促进的院外心脏骤停和难治性心室颤动复苏提高了出院生存率。未来的研究应侧重于识别 VA-ECMO 脱机和拔管后有不良事件风险的患者。

图 1:显示静脉-动脉体外膜肺氧合 (VA-ECMO) 回路各个组成部分的示意图。 流入插管将血液从体内输送到 ECMO 泵中,血液从那里被送至氧合器进行氧合。血液的温度经过优化,然后通过插入大口径动脉(最常见于股动脉)的流出套管送回体内。请单击此处查看此图的较大版本。

| 作者,年份 | 国家 | 设计 | 患者总数 (n) | 心源性休克的病因 | 院内生存率 (%) | ||

| 麻生, 201615 | 日本 | 回顾的 | 4658 | 缺血性心脏病、心力衰竭、心脏瓣膜病、心肌炎 | 26.4 | ||

| 史密斯,201752 | 全球 | 回顾的 | 2699 | 心肌炎、冠状动脉疾病、结构性心脏病、心脏移植后、心室后辅助装置 | 41.4 | ||

| 陈, 201753 | 台湾 | 回顾的 | 1141 | 心脏切开术后休克 | 38.3 | ||

| Thiagarajan, 201710 | 美国 | 回顾的 | 9025 | 综合 | 42 | ||

| Rastan, 201054 | 德国 | 回顾的 | 517 | 冠状动脉旁路移植术, 瓣膜手术, 冠状动脉旁路移植术加瓣膜手术, 胸器官移植, 其他 | 24.8 | ||

表 1:选择报告接受静脉动脉体外膜肺氧合 (VA-ECMO) 的心源性休克 (CS) 患者院内生存率的观察性研究。 这些研究强调,需要 ECMO 的患者的院内生存率仍然很低,在 24.8-42% 之间。

讨论

在该方案中,描述了难治性 CS 患者启动和维持 VA-ECMO 所涉及的各种步骤。还讨论了使用 VA-ECMO 的一些主要并发症、脱机参数和结局。

当其他管理策略无法为 CS 患者提供足够的血流动力学支持时,VA-ECMO 通常用作挽救疗法。插管涉及大口径血管通路,应谨慎进行,以尽量减少血管损伤和出血风险。一旦开始 VA-ECMO,应在心血管重症监护病房对患者进行监测,该病房配备有灌注师和护士,他们接受过处理 ECMO 回路的专业培训。应每天评估患者是否脱机,一旦心脏恢复或已确定更明确的治疗方法,应尽早进行拔管,以尽量减少并发症。

VA-ECMO 的利用率在过去二十年中大幅增加,适应症范围不断扩大。尽管可用性和使用率有所增加,但 CS 的死亡率仍然很高。患者选择对于确保明智地分配资源同时减轻与 VA-ECMO 相关的并发症至关重要。已经开发了几种评分系统来预测接受 VA-ECMO 的患者的生存率。静脉-动脉-ECMO (SAVE) 评分61 分后生存率是使用 ELSO 登记处的数据创建的,可用于预测 VA-ECMO 开始前患者的生存率。根据 CS 的病因、年龄、体重、急性器官衰竭(肾脏、肝脏和/或中枢神经系统)、慢性肾功能衰竭、插管持续时间、吸气峰压、舒张压和平均脉压、心脏骤停和碳酸氢盐值进行评分。根据 SAVE 评分,将患者风险分为 5 个不同的风险等级(I 级至 V 级)。较低的分数与较高的风险等级和较差的住院生存率相关。该评分系统也在 161 名澳大利亚患者中进行了外部验证,并显示出极好的鉴别力,接受手术特征曲线下面积为 0.90 (95% 置信区间为 0.85-0.95)。随后开发了包含乳酸的改良 SAVE 评分64,并显示在到达急诊科后 24 小时内接受 VA-ECMO 启动的患者具有出色的结果预测。最近开发并验证了另一种名为 PREDICT VA-ECMO 评分65 分的简化预后工具,该工具利用床旁生物标志物(乳酸、pH 值和碳酸氢盐浓度)在 1 、 6 和 12 小时进行测量。确定 VA-ECMO 后有不良事件风险的患者群体并随后使用更确定的疗法仍然是一个持续关注的领域。

有限的证据表明,在 CS 诊断后及早开始使用 VA-ECMO 可能会提高生存率13。Ostadal 等人的 ECMO-CS 试验未显示接受早期 VA-ECMO 治疗的患者与保守策略相比,任何原因导致的死亡率存在差异62。然而,这尚未以随机方式得到验证。测试新策略的价值及其成本效益以改善心源性休克不良结果 (EUROSHOCK) 试验 (ClinicalTrials.gov 标识符:NCT03813134) 是一项正在进行的随机临床试验,将评估 AMI 伴 CS 患者早期开始 ECMO 是否能提高 30 天生存率与标准治疗相比。同样,心源性休克体外生命支持 (ECLS-SHOCK) 试验 (ClinicalTrials.gov 标识符:NCT03637205) 将检查与在 AMI 并发 CS 中不使用 ECLS 相比,ECLS 联合血运重建和药物治疗是否有益。在本试验中,ECLS 将优先在血运重建之前开始。

VA-ECMO 的启动和维持需要大量的医疗保健资源,而这些资源可能仅在三级医院提供。当地社区与医疗保健系统合作,应专注于开发“辐条和枢纽模式”66,由外围较小的医院在诊断后立即将 CS 患者转诊到拥有有组织的 VA-ECMO 团队的中央三级医院。

披露声明

John Um 是 Abbott Laboratories 的顾问和 Medtronic 的顾问。Poonam Velagapudi 透露,他从 Abiomed、Medtronic、Opsens 和 Shockwave Medical 收取演讲费,以及参加 Abiomed 和 Sanofi 顾问委员会的费用。其他作者没有什么可披露的。

致谢

没有。

材料

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Amplatz Super Stiff guidewire | Boston Scientific | 46-500, 46-501, 46-502. 46-503, 46-504, 46-517, 46-519, 46-520, 46-523, 46-525, 46-526, 46-563, 46-564, 46-509, 46-510, 46-518, 46-524 | Allows delivery of catheters across tortuous anatomies |

| Impella | Abiomed | Impella 2.5, Impella CP, Impella 5.0, Impella 5.5, Impella RP | Percutaneously inserted left ventricular assist device that provides hemodynamic support in cardiogenic shock |

| Inflow Cannula | Surge Cardiovascular | FEM-V1020, FEM-V1022, FEM-V1024, FEM-V1026,FEM-V1028 | Removes deoxygenated blood from the central venous circulation into the ECMO circuit |

| Inflow Cannula | Medtronic Cardiopulmonary | Biomedicus 96600-019,021,023,025,027,029 | Removes deoxygenated blood from the central venous circulation into the ECMO circuit |

| Inflow Cannula | Medtronic Cardiopulmonary | Biomedicus Femoral Venous 96670 - 017,019, 021, 023 | Removes deoxygenated blood from the central venous circulation into the ECMO circuit |

| Inflow Cannula | Medtronic Cardiopulmonary | Biomedicus Multi-Stage Femoral Venous 96880-019,021,025 | Removes deoxygenated blood from the central venous circulation into the ECMO circuit |

| Inflow Cannula | Medtronic Cardiopulmonary | Biomedicus NextGen 96600 - 115, 117, 119, 121, 123, 125, 127, 129 | Removes deoxygenated blood from the central venous circulation into the ECMO circuit |

| Inflow Cannula | Medtronic Cardiopulmonary | Carmeda Biomedicus CB96605-015,017,019,021,023,025,29 | Removes deoxygenated blood from the central venous circulation into the ECMO circuit |

| Inflow Cannula | Medtronic Cardiopulmonary | Cortiva Biomedicus Femoral Venous CB96670-015,017,019,021 | Removes deoxygenated blood from the central venous circulation into the ECMO circuit |

| Inflow Cannula | Medtronic Cardiopulmonary | DLP Carmeda Venous CB75008, CB66112, CB66114, CB66116, CB66118, CB66120, CB66122,CB66124 | Removes deoxygenated blood from the central venous circulation into the ECMO circuit |

| Inflow Cannula | Getinge | Avalon Elite Bicaval - 10013, 10016, 10019, 10020, 10023, 10027, 10031 | Removes deoxygenated blood from the central venous circulation into the ECMO circuit |

| Inflow Cannula | Getinge | HLS Cannula Venous Bioline - BE PVS 1938, 2138, 2155, 2338, 2355, 2538, 2555, 2955 | Removes deoxygenated blood from the central venous circulation into the ECMO circuit |

| Inflow Cannula | Getinge | HLS Cannula Venous Softline - BO PVS 1938, 2138, 2155, 2338, 2355, 2538, 2555, 2955 | Removes deoxygenated blood from the central venous circulation into the ECMO circuit |

| Inflow Cannula | Getinge | HLS Cannula Venous - PVS 1938, 2138, 2155, 2338, 2355, 2538, 2555, 2955 | Removes deoxygenated blood from the central venous circulation into the ECMO circuit |

| Inflow Cannula | Medtronic Cardiopulmonary | Life Support Bio-Medicus Drainage Catheter and Introducers - LS96218 - 015, 017, 019, 021, 023, 025 ; LS96438 - 021, 023, 025, LS 96555 - 019, 021, 023, 025, LS 96355 - 021, LS96360 -023, 025, 027, 029 | Removes deoxygenated blood from the central venous circulation into the ECMO circuit |

| Inflow Cannula | Fresenius | Medos Femoral Cannula MEFKV 18,20,22,24,26,28 | Removes deoxygenated blood from the central venous circulation into the ECMO circuit |

| Inflow Cannula | Medtronic Cardiopulmonary | Medtronic 2 stage venous - 91228, 91240, 91246, 91236,91251 | Removes deoxygenated blood from the central venous circulation into the ECMO circuit |

| Inflow Cannula | Senko/Mera | PCKC-V-24, PCKC-V2-18, PCKC-V-18, PCKC-V2-20, PCKC-V-20, PCKC-V-22, PCKC-V2-24, PCKC-V-24 | Removes deoxygenated blood from the central venous circulation into the ECMO circuit |

| Inflow Cannula | TandemLife/Livanova | 29,31 Fr | Removes deoxygenated blood from the central venous circulation into the ECMO circuit |

| Inflow Cannula | Freelife Medical | FLK V19 B18, FLK V19 B18R, FLK VV 19R, FLK V20 B20, FLK V20 B20R, FLK V19 B20, FLK V19 B20R, FLK V20 B22, FLK V20 B22R, FLK V10S B22, FLK V19 B22, FLK V19 B22R, FLK V10 B22, FLK V10 B22R, FLK V10S B22R, FLK VV 23R, FLK V10S B24, FLK V10S B24R, FLK V10 B24, FLK V10 B24R, FLK V10S B26, FLK V10S B26R, FLK V10 B26, FLK V10 B26R, FLK VV 27R, FLK VV 31R | Removes deoxygenated blood from the central venous circulation into the ECMO circuit |

| Inflow Cannula | LivaNova | Sorin right angle venous - 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 22, 24, 28 | Removes deoxygenated blood from the central venous circulation into the ECMO circuit |

| Inflow Cannula | Terumo | CX-EB18VLX, CX-EB21VLX | Removes deoxygenated blood from the central venous circulation into the ECMO circuit |

| Outflow Cannula | Medtronic Cardiopulmonary | Biomedicus Arterial 96530 - 015,017, 019, 021, 023, 025, | Returns oxygenated blood to the body |

| Outflow Cannula | Medtronic Cardiopulmonary | Biomedicus Femoral Arterial 96570 - 015, 017, 019, 021 | Returns oxygenated blood to the body |

| Outflow Cannula | Medtronic Cardiopulmonary | Biomedicus NextGen Arterial 96530 -115, 117, 119, 121, 123, 125, 96570 - 115, 117, 119, 121 | Returns oxygenated blood to the body |

| Outflow Cannula | Medtronic Cardiopulmonary | Carmeda Biomedicus CB96535 - 015, 017, 019, 021, 023 | Returns oxygenated blood to the body |

| Outflow Cannula | Medtronic Cardiopulmonary | Cortiva Biomedicus Femoral Arterial CB96570 -015, 017, 019, 021 | Returns oxygenated blood to the body |

| Outflow Cannula | Getinge | PAS 1315, PAS 1515, PAS 1523, PAS 1717, PAL 1723, PAL 1923, PAL 2115, PAL 2123, PAL 2315, PAL 2323 | Returns oxygenated blood to the body |

| Outflow Cannula | Getinge | Bioline BE PAS 1315, BE PAS 1515, BE PAL 1523, BE PAL 1723, BE PAS 1915, BE PAL 1923, BE PAS 2115, BE PAL 2123, BE PAS 2315, BE PAL 2323, | Returns oxygenated blood to the body |

| Outflow Cannula | Getinge | Softline BO PAS 1315, BO PAS 1515, BO PAL 1523, BO PAS 1715, BO PAL 1723, BO PAS 1915, BO PAL 1923, BO PAS 2115, BO PAL 2123, BO PAL 2323 | Returns oxygenated blood to the body |

| Outflow Cannula | Fresenius | Medos Femoral Arterial Cannula; MEFKA 16, 18, 20, 22,24 | Returns oxygenated blood to the body |

| Outflow Cannula | Senko/Mera | PCKC-A-20, PCKC-A-16, PCKC-A-18 | Returns oxygenated blood to the body |

| Outflow Cannula | Freelife Medical | FLK A18 D16, FLK A18L D16, FLK A18L D16R, FLK A18 D16R, FLK A44 D18, FLK A44 D18R, FLK A18 D18, FLK A18L D18, FLK A18L D18R, FLK A18 D18R, FLK A44 D20, FLK A44 D20R, FLK A18 D20, FLK A18L D20, FLK A18L D20R, FLK A18 D20R, FLK A18 D22, FLK A18L D22, FLK A18L D22R, FLK A18 D24, FLK A18L D24, FLK A18L D24R, FLK A18 D24R | Returns oxygenated blood to the body |

| Outflow Cannula | LivaNova | Sorin arterial - 14, 17, 19, 21, 23 Fr | Returns oxygenated blood to the body |

| Outlflow Cannula | Medtronic Cardiopulmonary | Life Support Bio-Medicus Return Catheter and Introducers - LS96010-009, LS96010-011, LS96010-013, LS96010-015, LS96218-015, LS96218-017, LS96218-019, LS96218-021, LS96218-023, LS96218-025 | Returns oxygenated blood to the body |

| Oxygenator | Abbott | Eurosets | Deoxygenated blood from the inflow cannula is saturated with oxygen |

| Oxygenator | Getinge | MaquetHLS Set Advanced v 5.0, v 7.0, Maquet Quadrox iD | Deoxygenated blood from the inflow cannula is saturated with oxygen |

| Oxygenator | Medtronic | Nautilus | Deoxygenated blood from the inflow cannula is saturated with oxygen |

| Pump | Abiomed | Breethe | Generates force to deliver oxygenated blood back to the body |

| Pump | LivaNova | Alcard ALC 250 | Generates force to deliver oxygenated blood back to the body |

| Pump | Baxter | Century Roller Pump | Generates force to deliver oxygenated blood back to the body |

| Pump | Medtronic Cardiopulmonary | Biomedicus BP50, BP80 Centrifugal | Generates force to deliver oxygenated blood back to the body |

| Pump | Braile Biomedica | Safyre | Generates force to deliver oxygenated blood back to the body |

| Pump | Getinge | CiSet | Generates force to deliver oxygenated blood back to the body |

| Pump | Abbott | CentriMag | Generates force to deliver oxygenated blood back to the body |

| Pump | LivaNova | Cobe 6" Roller | Generates force to deliver oxygenated blood back to the body |

| Pump | Origen | FloPump 32 | Generates force to deliver oxygenated blood back to the body |

| Pump | Getinge | HIT Set Advanced Softline 5.0 and 7.0 | Generates force to deliver oxygenated blood back to the body |

| Pump | LivaNova | LifeSPARC | Generates force to deliver oxygenated blood back to the body |

| Pump | Senko/Mera | Centrifugal pump head | Generates force to deliver oxygenated blood back to the body |

| Pump | Getinge | HLS Set Advanced Bioline 5.0 and 7.0 | Generates force to deliver oxygenated blood back to the body |

| Tandem Heart | LivaNova | Tandem Heart LS | Percutaneously inserted left ventricular assist device |

参考文献

- Shah, M., et al. Trends in mechanical circulatory support use and hospital mortality among patients with acute myocardial infarction and non-infarction related cardiogenic shock in the United States. Clinical Research in Cardiology. 107 (4), 287-303 (2018).

- Goldberg, R. J., Spencer, F. A., Gore, J. M., Lessard, D., Yarzebski, J. Thirty-year trends (1975 to 2005) in the magnitude of, management of, and hospital death rates associated with cardiogenic shock in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a population-based perspective. Circulation. 119 (9), 1211-1219 (2009).

- Hochman, J. S., et al. Early revascularization in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. SHOCK Investigators. Should We Emergently Revascularize Occluded Coronaries for Cardiogenic Shock. The New England Journal of Medicine. 341 (9), 625-634 (1999).

- Hochman, J. S., et al. One-year survival following early revascularization for cardiogenic shock. JAMA. 285 (2), 190-192 (2001).

- Schumann, J., et al. Inotropic agents and vasodilator strategies for the treatment of cardiogenic shock or low cardiac output syndrome. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1), 009669 (2018).

- Léopold, V., et al. Epinephrine and short-term survival in cardiogenic shock: an individual data meta-analysis of 2583 patients. Intensive Care Medicine. 44 (6), 847-856 (2018).

- De Backer, D., et al. Comparison of dopamine and norepinephrine in the treatment of shock. The New England Journal of Medicine. 362 (9), 779-789 (2010).

- Strom, J. B., et al. National trends, predictors of use, and in-hospital outcomes in mechanical circulatory support for cardiogenic shock. EuroIntervention. 13 (18), 2152-2159 (2018).

- Stentz, M. J., et al. Trends in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation growth in the United States, 2011-2014. ASAIO Journal. 65 (7), 712-717 (2019).

- Thiagarajan, R. R., et al. Extracorporeal life support organization registry international report 2016. ASAIO Journal. 63 (1), 60-67 (2017).

- Lequier, L., Horton, S. B., McMullan, D. M., Bartlett, R. H. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation circuitry. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 14 (5), 7-12 (2013).

- Schmidt, M., et al. Blood oxygenation and decarboxylation determinants during venovenous ECMO for respiratory failure in adults. Intensive Care Medicine. 39 (5), 838-846 (2013).

- Sheu, J. J., et al. Early extracorporeal membrane oxygenator-assisted primary percutaneous coronary intervention improved 30-day clinical outcomes in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction complicated with profound cardiogenic shock. Critical Care Medicine. 38 (9), 1810-1817 (2010).

- Belohlavek, J., et al. Veno-arterial ECMO in severe acute right ventricular failure with pulmonary obstructive hemodynamic pattern. The Journal of Invasive Cardiology. 22 (8), 365-369 (2010).

- Aso, S., Matsui, H., Fushimi, K., Yasunaga, H. In-hospital mortality and successful weaning from venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: analysis of 5,263 patients using a national inpatient database in Japan. Critical Care. 20, 80 (2016).

- Asaumi, Y., et al. Favourable clinical outcome in patients with cardiogenic shock due to fulminant myocarditis supported by percutaneous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. European Heart Journal. 26 (20), 2185-2192 (2005).

- Religa, G., Jasińska, M., Czyżewski, &. #. 3. 2. 1. ;., Torba, K., Różański, J. The effect of the sequential therapy in end-stage heart failure (ESHF)-from ECMO, through the use of implantable pump for a pneumatic heart assist system, Religa Heart EXT, as a bridge for orthotopic heart transplant (OHT). Case study. Annals of Transplantation. 19, 537-540 (2014).

- Meani, P., et al. Long-term survival and major outcomes in post-cardiotomy extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for adult patients in cardiogenic shock. Annals of Cardiothoracic Surgery. 8 (1), 116-122 (2019).

- Bartos, J. A., et al. Improved survival with extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation despite progressive metabolic derangement associated with prolonged resuscitation. Circulation. 141 (11), 877-886 (2020).

- Brooks, S. C., et al. Part 6: Alternative techniques and ancillary devices for cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Circulation. 132 (18), 436-443 (2015).

- Guglin, M., et al. Venoarterial ECMO for adults: JACC scientific expert panel. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 73 (6), 698-716 (2019).

- Lorusso, R., et al. Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for refractory cardiogenic shock in elderly patients: Trends in application and outcome from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) Registry. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 104 (1), 62-69 (2017).

- Tehrani, B. N., et al. Standardized team-based care for cardiogenic shock. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 73 (13), 1659-1669 (2019).

- Pavlushkov, E., Berman, M., Valchanov, K. Cannulation techniques for extracorporeal life support. Annals of Translational Medicine. 5 (4), 70 (2017).

- Burrell, A. J. C., Ihle, J. F., Pellegrino, V. A., Sheldrake, J., Nixon, P. T. Cannulation technique: femoro-femoral. Journal of Thoracic Disease. 10, 616-623 (2018).

- Lamb, K. M., et al. Arterial protocol including prophylactic distal perfusion catheter decreases limb ischemia complications in patients undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 65 (4), 1074-1079 (2017).

- Pancholy, S. B., Shah, S., Patel, T. M. Radial artery access, hemostasis, and radial artery occlusion. Interventional Cardiology Clinics. 4 (2), 121-125 (2015).

- Hoeper, M. M., et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation watershed. Circulation. 130 (10), 864-865 (2014).

- Chung, M., Shiloh, A. L., Carlese, A. Monitoring of the adult patient on venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. The Scientific World Journal. 2014, 393258 (2014).

- Mungan, &. #. 3. 0. 4. ;., Kazancı, B. &. #. 3. 5. 0. ;., Ademoglu, D., Turan, S. Does lactate clearance prognosticates outcomes in ECMO therapy: a retrospective observational study. BMC Anesthesiology. 18 (1), 152 (2018).

- Su, Y., et al. Hemodynamic monitoring in patients with venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Annals of Translational Medicine. 8 (12), 792 (2020).

- Walter, J. M., Kurihara, C., Corbridge, T. C., Bharat, A. Chugging in patients on veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: An under-recognized driver of intravenous fluid administration in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Heart & Lung. 47 (4), 398-400 (2018).

- Kim, H., et al. Permissive fluid volume in adult patients undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation treatment. Critical Care. 22 (1), 270 (2018).

- Kalbhenn, J., Maier, S., Heinrich, S., Schallner, N. Bedside repositioning of a dislocated Avalon-cannula in a running veno-venous ECMO. Journal of Artificial Organs. 20 (3), 285-288 (2017).

- Weber, C., et al. Left ventricular thrombus formation in patients undergoing femoral veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Perfusion. 33 (4), 283-288 (2018).

- Tariq, S., Aronow, W. S. Use of inotropic agents in treatment of systolic heart failure. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 16 (12), 29060-29068 (2015).

- Thiele, H., Ohman, E. M., Desch, S., Eitel, I., de Waha, S. Management of cardiogenic shock. European Heart Journal. 36 (20), 1223-1230 (2015).

- Mason, D. T. Afterload reduction in the treatment of cardiac failure. Schweizerische Medizinische Wochenschrift. 108 (44), 1695-1703 (1978).

- Meani, P., et al. Modalities and effects of left ventricle unloading on extracorporeal life support: A review of the current literature. European Journal of Heart Failure. 19, 84-91 (2017).

- Taylor, T., Campbell, C. T., Kelly, B. A review of bivalirudin for pediatric and adult mechanical circulatory support. American Journal of Cardiovascular Drugs. 21 (4), 395-409 (2021).

- Geli, J., Capoccia, M., Maybauer, D. M., Maybauer, M. O. Argatroban anticoagulation for adult extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: A systematic review. Journal of Intensive Care Medicine. 37 (4), 459-471 (2022).

- Patel, B., Arcaro, M., Chatterjee, S. Bedside troubleshooting during venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Journal of Thoracic Disease. 11, 1698-1707 (2019).

- Cheng, R., et al. Complications of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for treatment of cardiogenic shock and cardiac arrest: a meta-analysis of 1,866 adult patients. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 97 (2), 610-616 (2014).

- Bonicolini, E., et al. Limb ischemia in peripheral veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a narrative review of incidence, prevention, monitoring, and treatment. Critical Care. 23 (1), 266 (2019).

- Moerman, A., Wouters, P. Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) monitoring in contemporary anesthesia and critical care. Acta Anaesthesiologica Belgica. 61 (4), 185-194 (2010).

- Chung, Y. S., et al. Is stopping heparin safe in patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation treatment. ASAIO Journal. 63 (1), 32-36 (2017).

- Kumar, A., Keshavamurthy, S., Abraham, J. G., Toyoda, Y. Massive air embolism caused by a central venous catheter during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. The Journal of Extra-Corporeal Technology. 51 (1), 9-11 (2019).

- Ortuno, S., et al. Weaning from veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: which strategy to use. Annals of Cardiothoracic Surgery. 8 (1), 1-8 (2019).

- Aissaoui, N., et al. Predictors of successful extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) weaning after assistance for refractory cardiogenic shock. Intensive Care Medicine. 37 (11), 1738-1745 (2011).

- Vida, V. L., et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: the simplified weaning bridge. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 143 (4), 27-28 (2012).

- Esposito, M. L., Jablonksi, J., Kras, A., Krasney, S., Kapur, N. K. Maximum level of mobility with axillary deployment of the Impella 5.0 is associated with improved survival. The International Journal of Artificial Organs. 41 (4), 236-239 (2018).

- Smith, M., et al. Duration of veno-arterial extracorporeal life support (VA ECMO) and outcome: an analysis of the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) registry. Critical Care. 21 (1), 45 (2017).

- Chen, S. W., et al. Long-term outcomes of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support for postcardiotomy shock. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 154 (2), 469-477 (2017).

- Rastan, A. J., et al. Early and late outcomes of 517 consecutive adult patients treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for refractory postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 139 (2), 302-311 (2010).

- Tsao, N. W., et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation-assisted primary percutaneous coronary intervention may improve survival of patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by profound cardiogenic shock. Journal of Critical Care. 27 (5), 1-11 (2012).

- Sakamoto, S., Taniguchi, N., Nakajima, S., Takahashi, A. Extracorporeal life support for cardiogenic shock or cardiac arrest due to acute coronary syndrome. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 94 (1), 1-7 (2012).

- Russo, J. J., et al. Left ventricular unloading during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in patients with cardiogenic shock. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 73 (6), 654-662 (2019).

- Ou de Lansink-Hartgring, A., de Vries, A. J., Droogh, J. H., vanden Bergh, W. M. Hemorrhagic complications during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation-The role of anticoagulation and platelets. Journal of Critical Care. 54, 239-243 (2019).

- Aubron, C., et al. Predictive factors of bleeding events in adults undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Annals of Intensive Care. 6 (1), 97 (2016).

- Chang, W. W., et al. Predictors of mortality in patients successfully weaned from extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. PLoS One. 7 (8), 42687 (2012).

- Schmidt, M., et al. Predicting survival after ECMO for refractory cardiogenic shock: the survival after veno-arterial-ECMO (SAVE)-score. European Heart Journal. 36 (33), 2246-2256 (2015).

- Ostadal, P., et al. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in the Therapy of Cardiogenic Shock: Results of the ECMO-CS Randomized Clinical Trial. Circulation. , (2022).

- Yannopoulos, D., et al. Advanced reperfusion strategies for patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and refractory ventricular fibrillation (ARREST): a phase 2, single centre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 396 (10265), 1807-1816 (2020).

- Chen, W. C., et al. The modified SAVE score: predicting survival using urgent veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation within 24 hours of arrival at the emergency department. Critical Care. 20 (1), 336 (2016).

- Wengenmayer, T., et al. Development and validation of a prognostic model for survival in patients treated with venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: the PREDICT VA-ECMO score. European Heart Journal. Acute Cardiovascular Care. 8 (4), 350-359 (2019).

- Huitema, A. A., Harkness, K., Heckman, G. A., McKelvie, R. S. The spoke-hub-and-node model of integrated heart failure care. The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 34 (7), 863-870 (2018).

转载和许可

请求许可使用此 JoVE 文章的文本或图形

请求许可探索更多文章

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

版权所属 © 2025 MyJoVE 公司版权所有,本公司不涉及任何医疗业务和医疗服务。